Lawful Basis for Processing under the GDPR

As dreadful as it sounds, take a moment to think about your email inbox. Forget about the emails from colleagues and family members that you have yet to answer. Instead, think about that one sender who got your email address - and you're not sure how - and now bombards you with daily messages.

You don't know where it comes from or what the point of it is. Maybe it's a word-of-the-day or a trivia email. Maybe you looked at a pair of shoes once and now can't escape the retailer until you buy them. You might have clicked unsubscribe a few times, or even pointlessly replied to the sender's address, telling them to take you off their list.

Feel the annoyance and confusion that the one email - one of the hundreds that you get each week - wreaks upon your life.

You'll be glad to know that if you are a resident of the EU, the sender is in violation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and therefore subject to fines (and bureaucratic headaches).

Why?

The GDPR requires all data processors to have what's called a "lawful basis" for any processing. And harvesting email addresses like the sender above? It doesn't make the cut of compliance.

What is data processing? Are you a data processor? And what do you need to do to make sure you use data legally? Keep reading to learn more about what it means to handle data in the GDPR world.

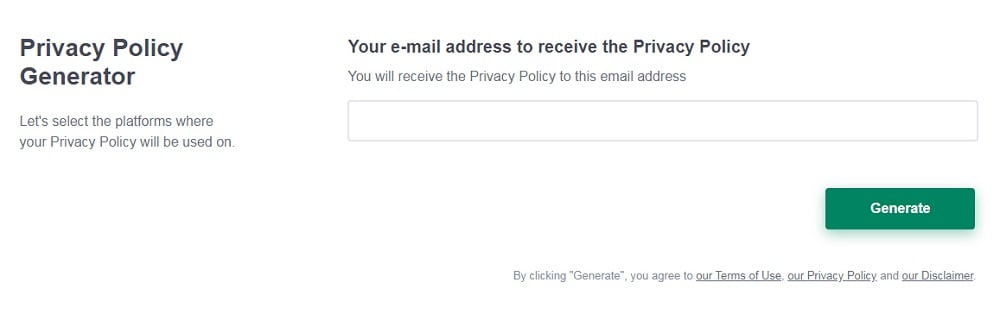

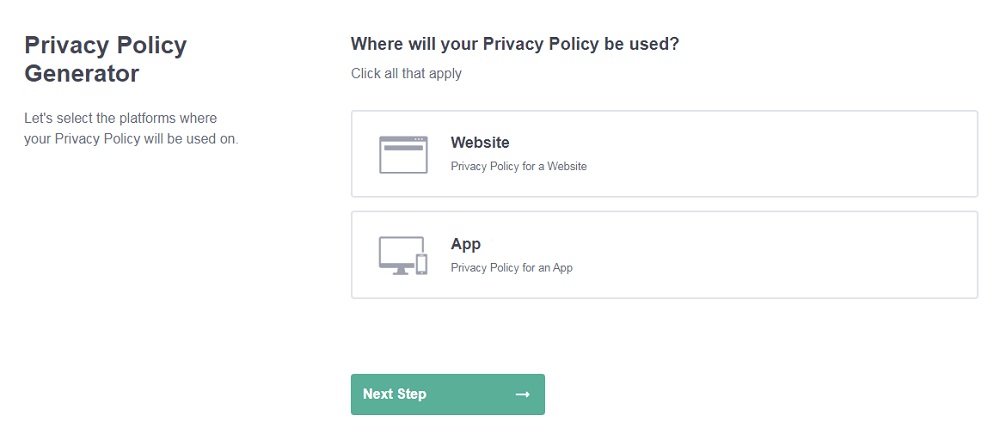

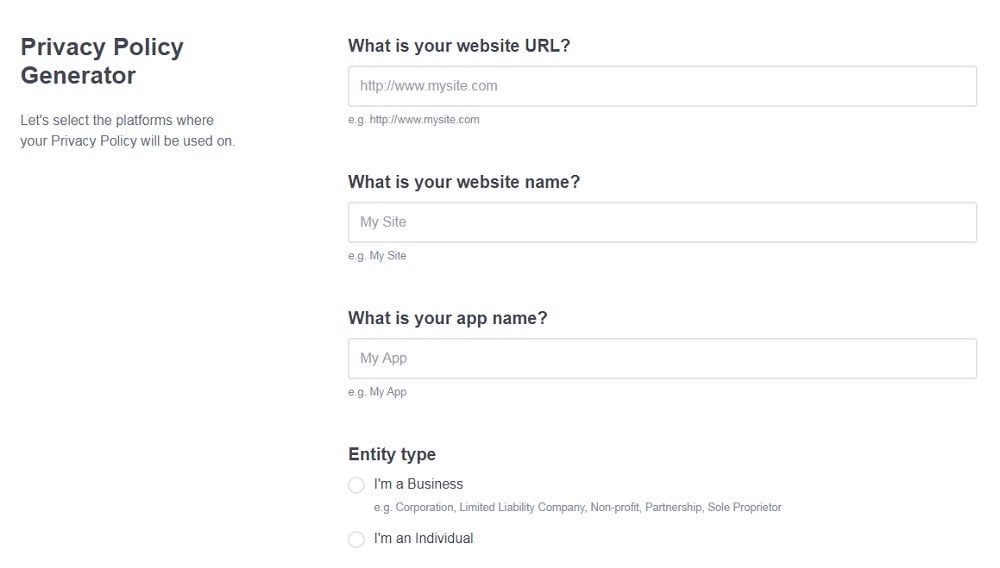

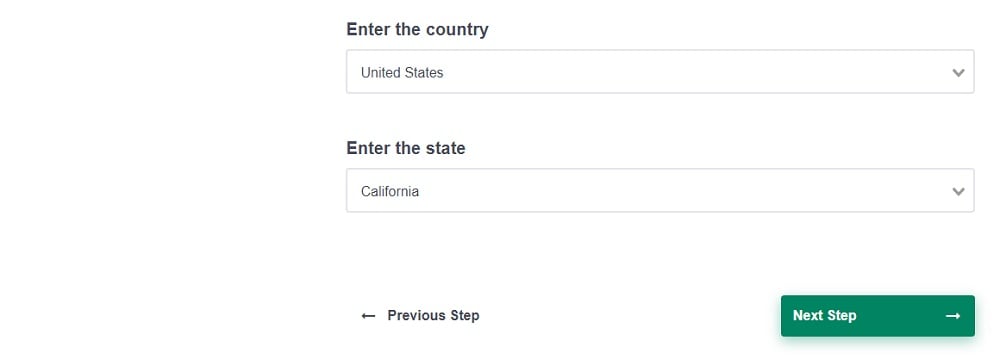

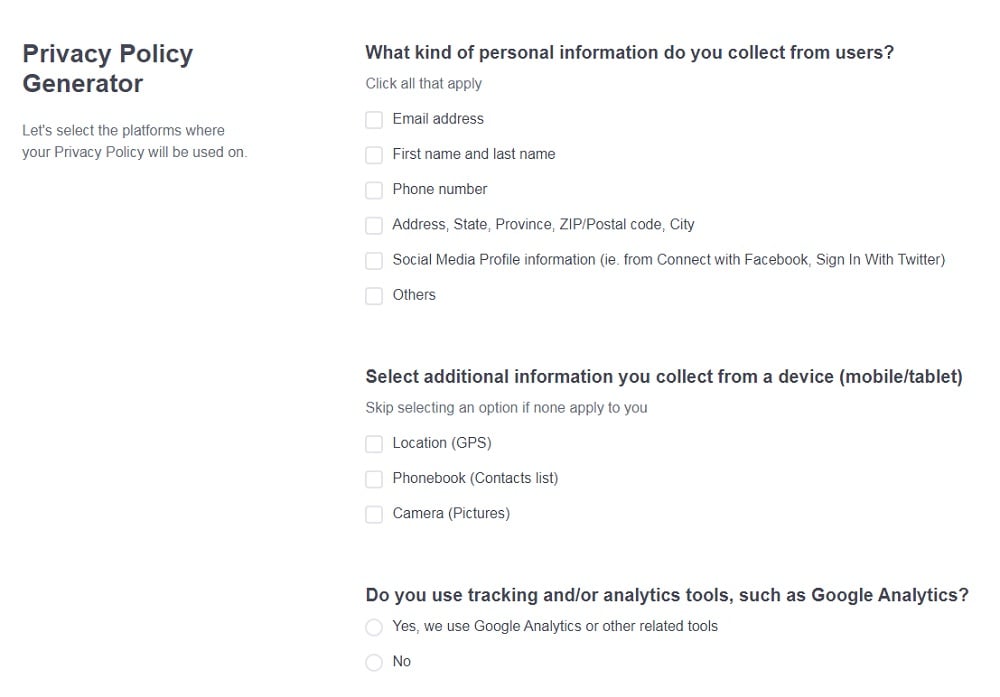

Need a Privacy Policy? Our Privacy Policy Generator will help you create a custom policy that you can use on your website and mobile app. Just follow these few easy steps:

- Click on "Start creating your Privacy Policy" on our website.

- Select the platforms where your Privacy Policy will be used and go to the next step.

- Add information about your business: your website and/or app.

- Select the country:

- Answer the questions from our wizard relating to what type of information you collect from your users.

-

Enter your email address where you'd like your Privacy Policy sent and click "Generate".

And you're done! Now you can copy or link to your hosted Privacy Policy.

- 1. What is Data Processing?

- 2. What's Considered "Data Processing" Under the GDPR?

- 3. When Can You Process Data?

- 4. The Six Lawful Bases for Processing Data

- 4.1. Consent

- 4.2. Legal Obligation

- 4.3. Contractual Basis

- 4.4. Legitimate Interests

- 4.5. Vital Interests

- 4.6. Public Task

- 5. What's the Best Lawful Basis to Use?

- 6. When Do You Need to Ask for Consent?

- 6.1. What Does Consent Look Like?

- 7. Summary

What is Data Processing?

The GDPR concerns itself with two groups: data controllers and data processors. These are very clinical terms to describe something that most businesses with a website or mobile app do every day.

Data processing is effectively turning raw data (like IP addresses, signal data, email addresses, etc.) into something useable. Some of the classic data processing transactions are payroll processing or advertising analytics. It can even be as simple as collecting an email address and adding it to your newsletter list on MailChimp.

It takes place across six stages beginning with data collection.

Data collection brings out raw data from available sources (including warehouses) before undergoing a 'cleaning' phase for processing. During the cleaning phase, it's checked for errors and organized to ensure you only process high-quality (useful) data.

Armed with a useable data set, you put it into your processing mechanism. A very popular example is Salesforce and other CRMs.

The program then 'processes' the data to interpret it. Each one uses the data differently based on its functions, proprietary algorithms, and your needs. It then generates the data into something you can read - the stuff of weekly reports and actionable decisions.

At the end, you store the data for future use either now or in the more distant future.

What's Considered "Data Processing" Under the GDPR?

To understand what steps you need to employ, you need to know two things:

- The GDPR's definition of data

- The GDPR's definition of processing

Article 4(1) says that personal data is:

"Any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person ('data subject'); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person."

The GDPR defines "data processing" in Article 4(2) of the text:

"'Processing' means any operation or set of operations which is performed on personal data or sets of personal data, whether or not by automated means, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation, or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction."

In other words, if you collect and process data using the six stages described above and the data you collect can identify a person - directly or indirectly - then your data processing falls under the scope of the GDPR.

But before you can even think about collecting data, you need to determine whether you have a right to process it under the law.

When Can You Process Data?

The GDPR doesn't allow you to process any data you want for any reason you can think of. Those notions belong in the past - the Wild Wild West of data processing.

Rather, the law requires you to both name and describe the appropriate lawful basis for processing each major category of data as well as special categories of data laid out in Article 9.

You can use one or several of the lawful bases, but they must be rooted in your actual data processes.

Why is there a need for a lawful basis? It comes back to the GDPR's commitment to transparency, accountability, and data minimization principles. For too long, some data processors collected data recklessly - and often collected warehouses worth of data not to use but simply to have.

Holding on to data is a risk in itself. Continuing to store huge amounts of data - data you don't intend to use - increases the risk to every data subject's privacy both in terms of potential breaches and in their general privacy. In other words, big internet companies don't need to know every piece of data available from an individual without there being a need for it.

It also cracks down on the sale and sharing of data with third parties, which also risks the data subject's right to privacy.

So, what are the lawful bases identified by the GDPR?

The Six Lawful Bases for Processing Data

You can only process data under the GDPR if you can produce evidence (both written and procedural) of at least one of the six named lawful bases, which include:

- Consent

- Legal obligation

- Contractual obligation

- Legitimate interest

- Vital interest

- Public task

Let's take at look at each one and what it means.

Consent

Consent is perhaps the strongest of the lawful bases because it speaks to the mission of the GDPR: to put the data subject back in control of their own data.

In essence, it requires you to ask the data subject for permission to process their data before you collect it. Consent can't be implied. You can't assume that they agree to your data processing just because they use your site.

Article 4(11) provides the full definition of consent:

"Consent of the data subject means any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject's wishes by which he or she by a statement or clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her."

Additionally, it needs to meet new requirements as defined in Article 7, which we'll lay out later.

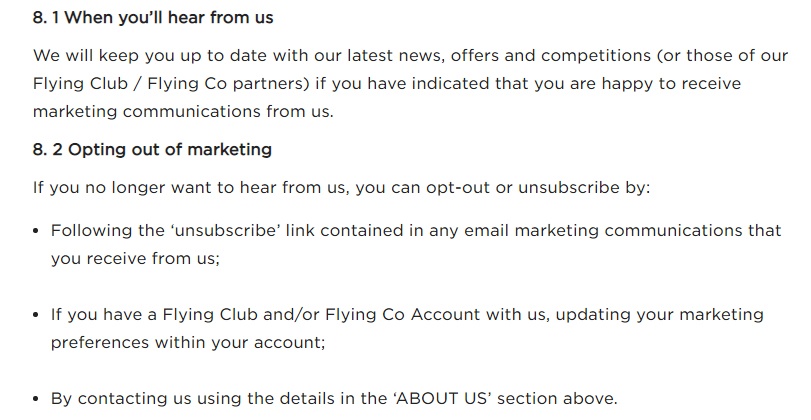

You don't need to add consent as a legal basis to your Privacy Policy. However, you do need to describe how data subjects can withdraw their consent and how to opt-out of marketing.

Virgin Atlantic describes the exact mechanisms that data subjects can use to opt-out of their marketing or communications:

Legal Obligation

The legal obligation basis states that you need to process personal data to comply with the law. For example, a bank may need to process passport numbers or Social Security numbers to meet federal standards for proof of identification as well as anti-money laundering statutes.

However, if you run a social media platform, you don't require these sensitive pieces of data because there's no law saying so. As a result, you'd need to rely on a different basis.

When you quote your legal obligation, it's a good idea to also state what statutes or agencies you report to. For example, TSB, a British bank, states it must collect data to provide information to HMRC (the tax authority) and prevent fraud:

Contractual Basis

The contractual basis exists to protect processors who require data to fulfill a contract.

In most cases, the data you need to fulfill a contract comes from the basis of your legitimate interests. However, for data that doesn't apply to every customer or when you need to meet a contract that differs from the norm, you can add the contractual basis.

Anglian Water, a water provider in England, added it to its Privacy Policy to cover certain (but unnamed) processing activities:

Legitimate Interests

Legitimate interests refers to both you and your data subject's legitimate interests, and it is the most opaque of the lawful bases. For example, you might collect certain data to prevent fraud, which is in both your interests. However, Recital 47 says that you can also use legitimate interest for direct marketing purposes.

As a general rule, you should not consider 'legitimate interest' a free-for-all, and remember that you still have other rights to uphold and request consent for specific activities (like direct marketing). The basis is most likely to become clearer over time.

At the moment, the best way to determine whether you can use the legitimate interest basis is to ask whether you can complete your processing without the personal data. If the answer is yes, then legitimate interest won't usually apply. You should also be able to list your legitimate interests in writing in your Privacy Policy as Marks and Spencer does here:

Vital Interests

The vital interests basis refers to processing that is absolutely necessary but also a case where consent won't apply.

The given interpretation of the basis says that you rely on it if you need it to protect someone's life but you can't otherwise get consent for the processing (either they can't or won't provide it).

Most businesses won't rely on vital interest at all. Healthcare organizations (namely emergency medical care providers) and public bodies may be the only ones who use this basis.

For example, St. Vincent's teaching hospital makes it clear that anyone receiving treatment or care at the hospital must provide data regardless of whether they consent:

Public Task

Public task refers to the need to collect data in the public interest, such as during a task by a public authority.

It usually doesn't apply to private companies, but it also doesn't require statutory power to process the data.

Like other lawful bases, the processing must be necessary. You can't claim this basis if you can get away without processing the data.

What's the Best Lawful Basis to Use?

Although consent tends to be the strongest because it is the most transparent and least intrusive, there is no actual hierarchy involved. Each legal basis is as strong as the other as long as you meet the requirements both in your argument and in your data processing.

Remember that all are subject to scrutiny from regulators and supervisory authorities, so be sure to choose carefully and create the documentation required to defend your decision, if called upon.

When Do You Need to Ask for Consent?

If you decide to rely on consent for any of your data processing, you must make sure your consent matches the expectations laid out in the GDPR.

Article 7 clarifies the conditions under which you can lawfully seek and process consent.

First, that means asking for permission before collecting any data. If you already collected the data prior to the GDPR, you need to re-confirm consent.

Second, you need to demonstrate that data subjects provided consent. This is where the "clear affirmative action" or written declaration mentioned in Article 4 comes in. However you collect proof of consent, you need to do so in a way that is "in an intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language."

In other words, you can sneak consent into a form or use legalese to describe your actions. Trying to outwit your data subject means you don't have legally have consent and therefore don't have a lawful basis to hold the data. And it can land you in hot water: just ask Google.

Third, you must acknowledge the data subject's right to withdraw their consent whenever they want. You also need to make it as easy to withdraw consent as it is to provide it. In other words, if giving consent is a click of a button, then withdrawing consent should also be as easy as clicking a button.

Fourth, consent must be freely given. You can't withhold their service for not giving you consent to process their data. As above, it also means you can't trick them into consenting. They should know what they consent to, including whether you collect data on behalf of a third party and who that third party is.

Finally, consent must always be specific. It shouldn't be lumped in with other mechanisms. It should also be granular so that they can agree to specific types of data processing.

A common example of this lies in direct marketing. Agreeing to Terms of Service should not also require the data subject to agree to email marketing. These two consent mechanisms need to be distinct because they are for two different items.

What Does Consent Look Like?

What do all the conditions of consent look like in practice?

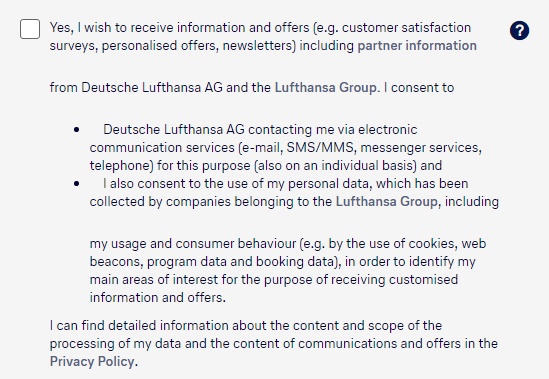

Lufthansa provides a very helpful example on its page where it collects information for account creation.

By checking the box (an affirmative, actionable consent), the data subject clearly signs up for email marketing both from Lufthansa and its partners (who are named in a hyperlink).

At the bottom of the form, you agree to Lufthansa's Privacy Policy by clicking 'Create profile.' However, you can leave the box unchecked to opt-out of direct marketing without impacting your ability to create an account:

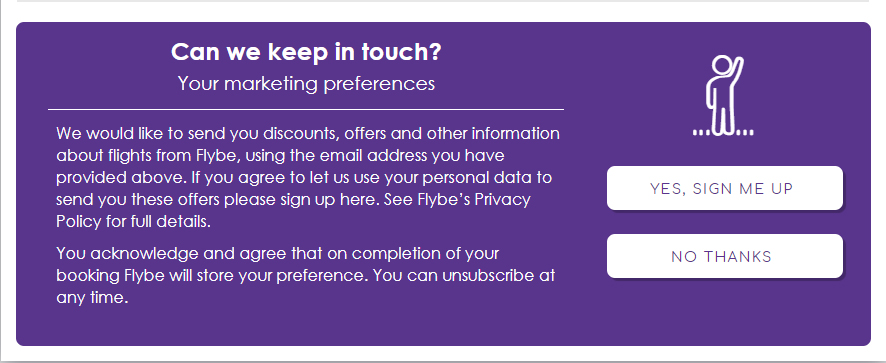

FlyBe also provides another example of granular, informed consent. Within its check-out page, it offers an entire box dedicated to opt-in into data processing for email marketing.

It explains exactly what the data subject is signing up for and informs the subject where they can learn more and of their rights.

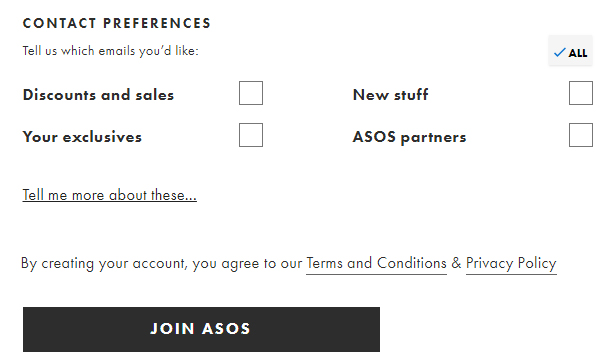

Our final example is another email marketing mechanism, this time from ASOS, an ecommerce giant. ASOS goes out of its way to allow data subjects to agree to processing (for direct marketing) in specific categories or none of the above. All they need to do is tick the boxes and then click 'Join Asos' to provide consent:

Summary

If you fall under the scope of the GDPR, then you need to have a legal basis to process data. Even sending direct marketing emails requires consent, which means that those spam emails that drive you crazy are a violation of privacy law - at least in the EU.

Most businesses will use the legitimate interest or consent bases for processing the vast majority of their data. Heavily regulated businesses or those that deal with life-or-death situations may also use the legal obligation or vital interest bases.

Whatever legal basis you choose, make sure that it applies fully to your processing activities. Additionally, remember to keep the appropriate documentation including adding the relevant provisions to your Privacy Policy.