GDPR Consent Examples

The EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a privacy law that sets a high standard for consent. Under the GDPR, consent really means consent. Certain methods that have previously been used to get consent are no longer valid.

Let's see how your company can make sure it's obtaining consent in the right way, and for the right things.

- 1. What is the GDPR?

- 1.1. Who Needs to Comply with the GDPR?

- 1.2. What Does the GDPR Cover?

- 2. How Consent is Different Under the GDPR

- 2.1. Implied Consent

- 2.2. Express Consent

- 2.3. Five Elements of Consent Under the GDPR

- 2.4. When is Consent Required?

- 3. How to Obtain Consent Under the GDPR

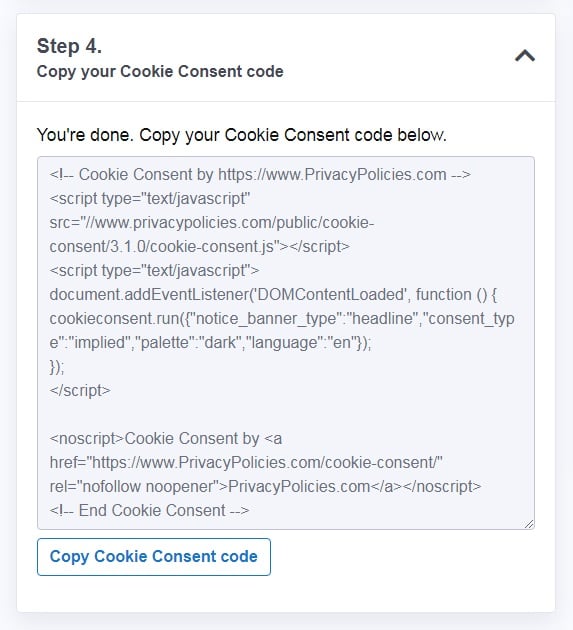

- 3.1. Consent for Cookies

- 3.2. Consent for Sending Marketing Material

- 3.3. Consent for Third Party Marketing

- 3.4. The Sixth Element of Consent - Easily Withdrawn

- 3.5. Consent on a Mobile App

- 4. Summary - Gaining Consent Under the GDPR

What is the GDPR?

The GDPR is almost certainly the strictest privacy law in the world. But stringent EU privacy and data protection laws are nothing new. The Data Protection Directive, an older privacy law that the GDPR replaces, and the ePrivacy Directive, sometimes known as the "cookie law," were already providing people in the EU with a high level of privacy protection.

The GDPR has had a particularly significant impact, partly because it also applies to non-EU companies.

Who Needs to Comply with the GDPR?

The GDPR applies to your company whether you're based in the EU or not so long as you're:

- Offering goods and services to people in the EU. This is regardless of whether you're pursuing a profit.

- Monitoring people's behavior in the EU. This can include "profiling" people - trying to predict how they might act based on observations about their past behavior. This is actually very common as it's what many advertising cookies do.

What Does the GDPR Cover?

Whenever your company is processing personal data, it needs to comply with the GDPR. Processing personal data is something companies do every day.

"Personal data" is information that can be used to identify a person. If you're wondering whether something might qualify as personal data, you can bet that it probably does.

Dynamic IP addresses, for example, have been found by the EU's top court to constitute personal data. This is because a dynamic IP address can theoretically be combined with other information to identify a person. Certain cookies also qualify.

"Processing" personal data means doing something with it. Again, if you're wondering whether something qualifies as processing, chances are that it does.

Aside from the obvious things like taking payment details or compiling a mailing list, an action such as storing someone's IP address in your web server's log files might also constitute "processing personal data."

How Consent is Different Under the GDPR

There are two types of consent in most privacy laws: implied and express. Whereas most privacy laws recognize both types of consent, implied consent does not exist in the GDPR. It is much harder to demonstrate that you have a customer's consent under the GDPR than it is under other privacy laws.

These can go by different names. For example, in Australia's Spam Act 2003 commercial email law, implied consent is called "inferred consent." And in the United States, the CAN-SPAM privacy law calls express consent "affirmative consent."

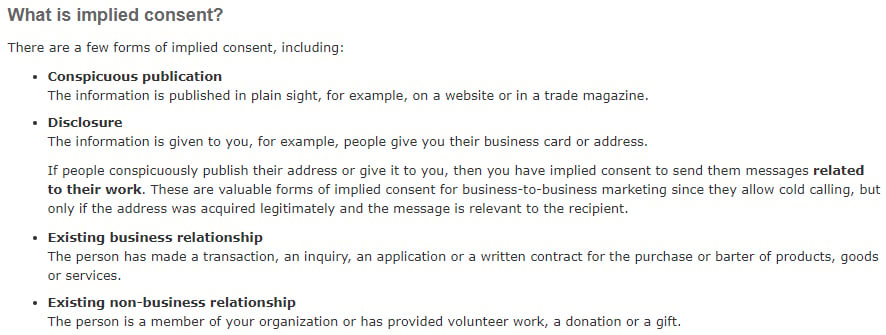

Implied Consent

Essentially, "implied consent" means that you have reason to believe that a person would give you their consent if you asked for it.

Implied consent might exist in a relationship between a customer and a business. If someone is regularly purchasing products from a business, that business might reasonably believe that they have consented to receive marketing emails from them. The business will almost always have to offer the customer an "opt-out" from such communication via an unsubscribe facility.

For example, in Canada's Anti-Spam Law (CASL), a Canadian privacy law, implied consent automatically exists under certain conditions. The Government of Canada explains this on its website:

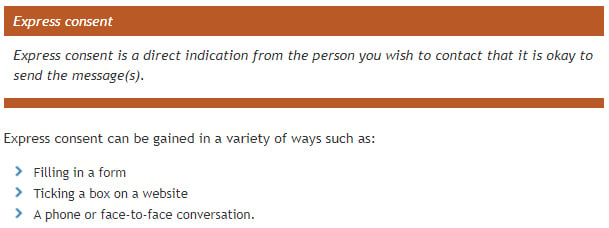

Express Consent

Express consent is what "consent" means under the GDPR. You ask for someone's consent, they understand the question and the implications, and they make a genuine choice.

New Zealand's Unsolicited Electronic Messages Act 2007 spam law recognizes both express and implied consent. Here's how the New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs characterizes express consent to send commercial emails:

Five Elements of Consent Under the GDPR

Article 4 of the GDPR defines consent as "any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous [...] clear affirmative action" by which a person gives permission for their personal data to be processed in a particular way.

We can break that down into five elements:

- Freely given - the person must not be pressured into giving consent or suffer any detriment if they refuse.

- Specific - the person must be asked to consent to individual types of data processing.

- Informed - the person must be told what they're consenting to.

- Unambiguous - language must be clear and simple.

- Clear affirmative action - the person must expressly consent by doing or saying something.

If you're missing any one of these five elements, you don't have consent under the GDPR.

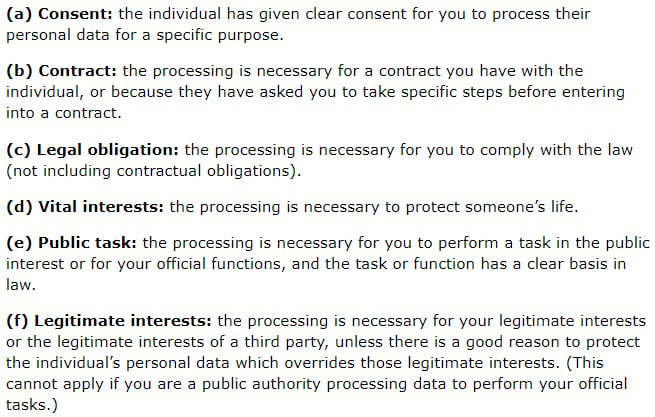

When is Consent Required?

One of the myths circulating about the GDPR is that it requires consent for all types of data processing. This is not true. Consent is only one of the six lawful bases for processing personal data provided by the GDPR. They are summarized by the Information Commissioner's Office (the UK's Data Protection Authority):

Generally speaking, you shouldn't ask for consent if:

- You're carrying out a core service (use contract instead).

- You're required to process personal data by law (legal obligation).

- You're processing personal data to the benefit of your company or others in a way that your users would reasonably expect, with minimal risk and impact on individuals (legitimate interests).

You should ask for consent where you are offering a genuine choice over a non-essential service. Typical examples include:

- Using tracking/advertising cookies

- Sending marketing emails or newsletters

- Sharing personal data with other companies for commercial purposes

How to Obtain Consent Under the GDPR

You must implement the five elements of consent every time you ask for consent from your users.

Consent for Cookies

A lot of cookie banners have gone up since the GDPR was implemented. Many of them would be fine under a system that allows "implied" consent, but remember - the GDPR only recognizes express consent.

Then there are cookie banners which almost ask for consent but still fall short, like this example from the Southbank Centre:

![]()

Consent is not even sought in this example and cookies are placed by default. Users are directed to more information, which informs them how to opt out of cookies.

But remember the five elements. Consent is not freely given under this approach. Nor is it unambiguous, or made via a clear affirmative act.

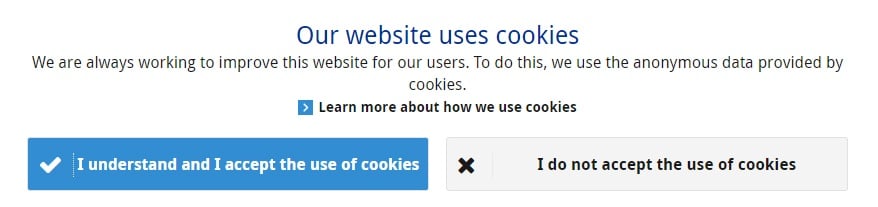

Here's an example of a much better cookie notice from the European Central Bank:

The five elements are all here. Consent is:

- Freely given - there is emphasis on neither "accept" nor "do not accept."

- Informed - the user is told the reason for the processing and invited to learn more.

- Unambiguous - the language is clear and easy to understand.

- Specific - the user is only invited to consent to one type of data processing.

- Obtained via a clear, affirmative action - the user must click "I understand and I accept."

Note that an additional "I agree" checkbox is not required. One click is enough for one consent request.

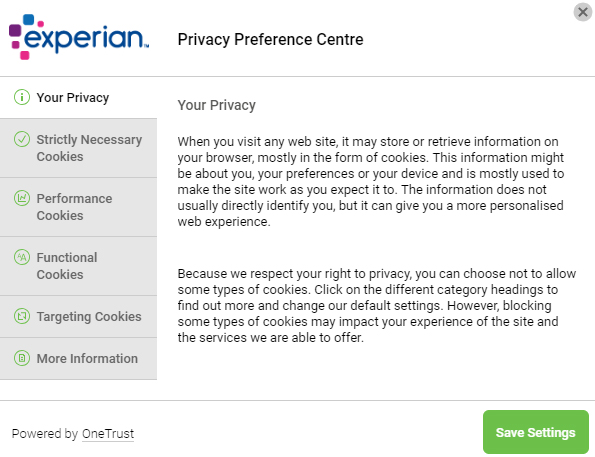

This is quite a simple case - the European Central Bank website only uses very basic cookies. Here's an example from Experian of how you can request specific consent for different types of cookies:

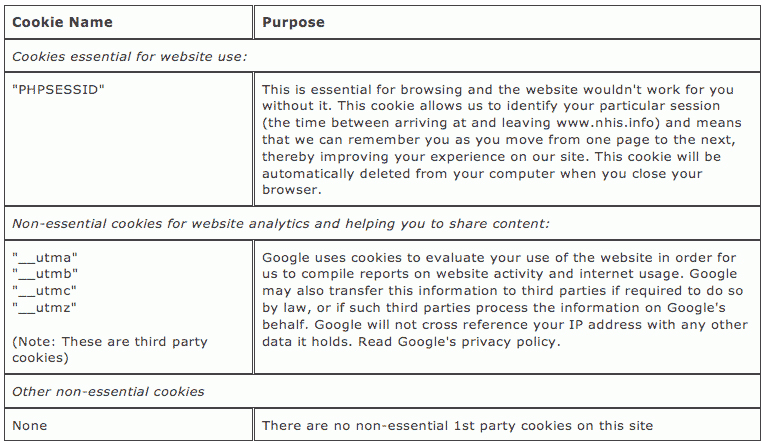

You must inform your users about your use of cookies in your Privacy Policy (or Cookie Policy). Here's how Makermet explains the different types of cookies it uses:

Remember that consent isn't just about what you say, it's about what you do. Don't set advertising cookies unless your users have consented to them.

Consent for Sending Marketing Material

The GDPR should signal the end of the pre-ticked box, a tactic used for many years by companies hoping to trick subscribers into accidently joining their mailing list.

It might seem like there is a quite minor distinction between asking someone to tick a box and asking some to untick a box. However, "failing to untick a box" does not comply with any of the five elements of consent under the GDPR. Therefore, this can't be used to demonstrate that you have a person's consent.

You can easily implement the five elements of GDPR consent when asking people to sign up to your mailing list. Here's an example from Dynastar:

How does this measure up against the five elements?

- Freely given - the user has an obvious choice as to whether to provide their email address.

- Informed - the user is told the reason for the processing, however the word "marketing" is in the small print. The user is invited to read Dynastar's Privacy Policy.

- Unambiguous - the language is clear and easy to understand.

- Specific - it could be clearer that the newsletter is a form of marketing, but this is a minor point.

- Gained via a clear, affirmative act - entering their email and clicking "subscribe to newsletter" is a clear affirmative act.

This is a pretty good example of a mailing list signup mechanism.

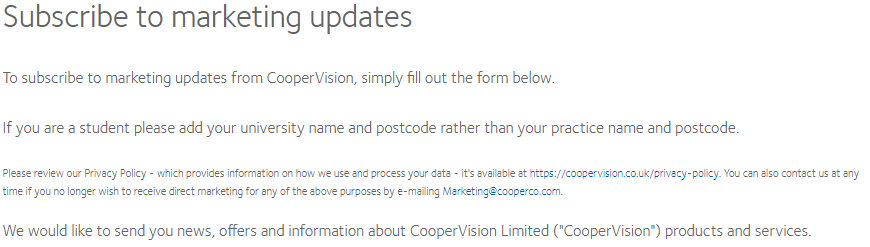

Here's another example from Cooper Vision. Firstly, the user is told exactly what they're signing up to:

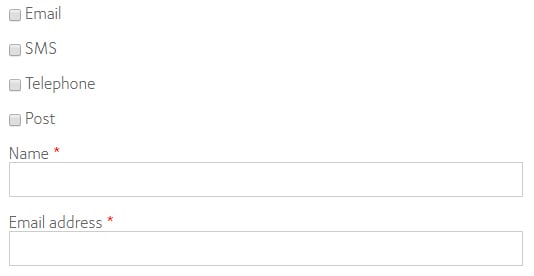

Then the user is offered choices about how they receive the information:

Cooper Vision's consent request easily fulfills the GDPR's requirements.

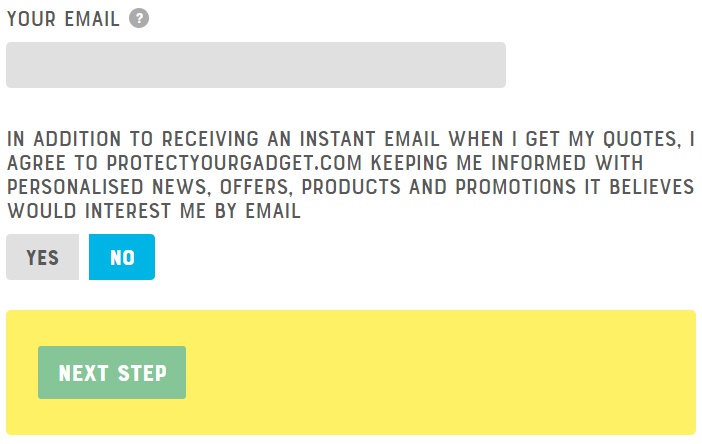

Often consent for sending marketing materials is gained when the user is signing up for some other service or interacting with your company in some other way. Here's an example from Protect Your Gadget. At this point, the user is about to sign up to receive an insurance quote:

So long as it's clear that this is a separate option, and the default answer is "no," then there is no problem here. A problem arises if a user subscribes to marketing material without realizing they've done so or actively doing so.

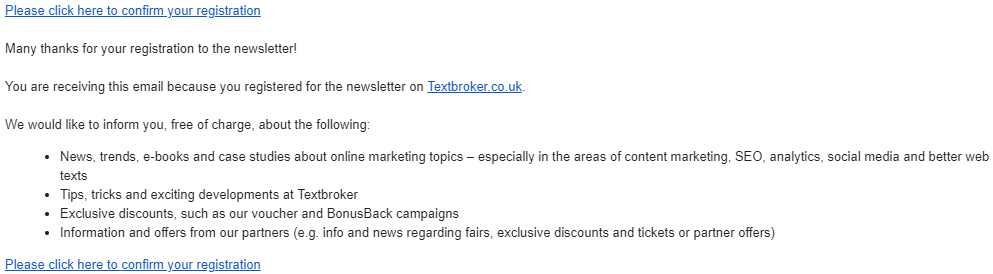

On that note, it's also good practice to implement a "double opt-in" whereby users are asked to confirm their subscription via a validation email. Here's an example from Textbroker:

Consent for Third Party Marketing

There are two ways you might engage your users with marketing from other companies. You might send third-party marketing material to them directly, or you might share their contact details with other companies.

Neither case is forbidden under the GPDR. But as in all aspects of data processing, you must be clear and transparent. You'll almost always need to seek consent for these purposes.

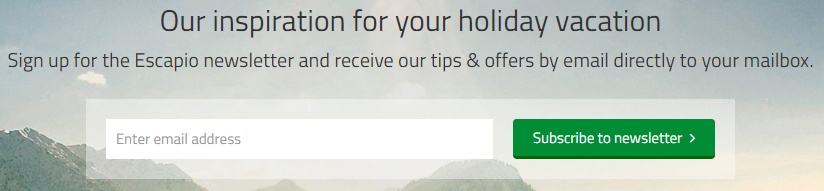

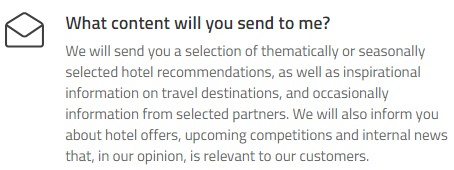

You shouldn't bundle your consent request for sharing personal data with other consent requests. Take a look at this consent request from Escapio:

Users are told that they are signing up for "our [Escapio's] tips and offers." But scrolling down the page reveals more:

The user will be receiving third-party marketing information, hotel recommendations, competitions - more than just "tips and offers" from Escapio. Consent for all of these things is bundled into one request. This appears to fall short of the requirement that consent is "specific."

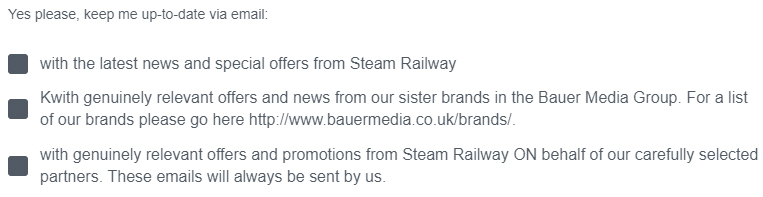

Here's an example of an unbundled consent request from Steam Railway:

These are three different purposes for which the users' email address will be put. Therefore, it's appropriate to ask for consent in three different ways with three different checkboxes.

Note: Remember to never pre-tick any checkboxes you use when requesting any sort of consent.

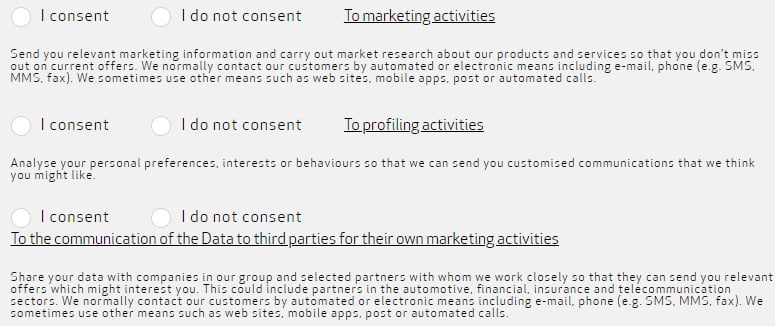

Here's another example of unbundled consent requests from Alfa Romeo:

This is a great example of consent that is freely given, informed, specific, unambiguous, and given via a clear affirmative action.

The Sixth Element of Consent - Easily Withdrawn

There is a sixth requirement under the GDPR - consent must be easy to withdraw.

Of course, you should include an unsubscribe facility in your marketing emails. Here's how Hermes does this:

Other means to withdraw consent must be clearly explained in your Privacy Policy. Here's how Bauer Publishing does this:

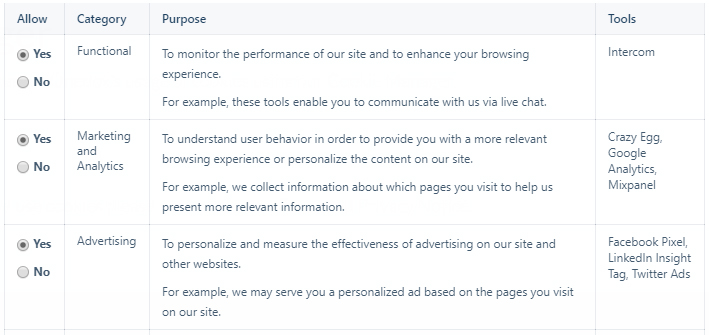

Cookies can often be managed via a "cookie manager." Here's an example from Onedox:

Note that many of these settings should be "off" by default.

Consent on a Mobile App

The principles of obtaining consent are the same on mobile apps as they are in any other medium.

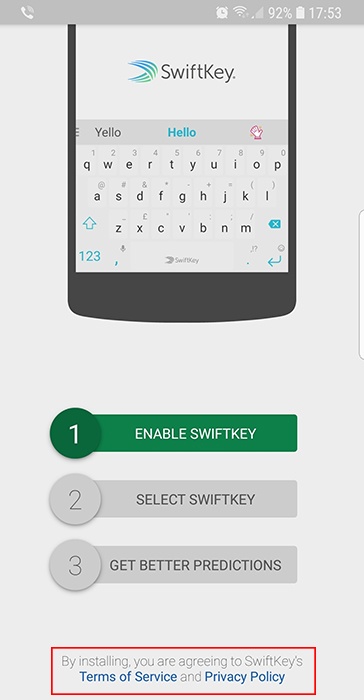

Here's an example of a consent request from Swiftkey's mobile app:

Swiftkey purports to obtain consent when the user installs the app. Installing the app is arguably not an unambiguous or clear affirmative act that necessarily shows consent.

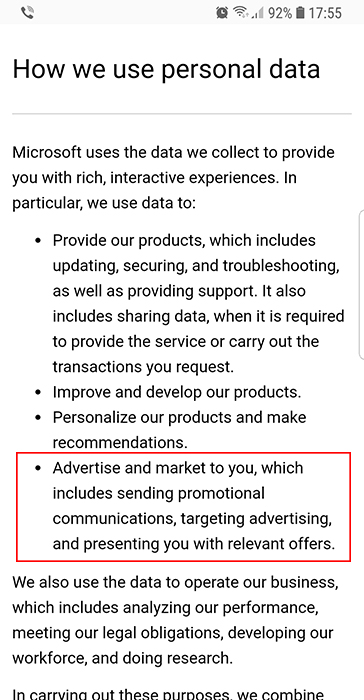

This is not necessarily a problem if the app wouldn’t collect information that will be used for targeting advertising (which require specific consent). A quick look at the Swiftkey's Privacy Statement (operated by Microsoft) indicates that specific consent should ideally be sought because the collected information is used for targeting advertising.

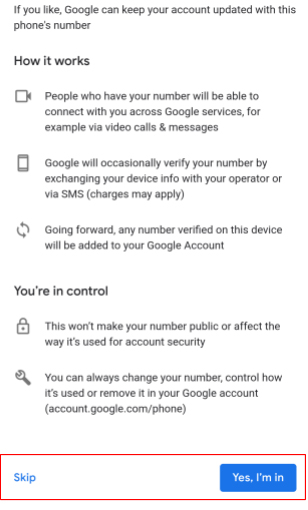

It's common on mobile apps for information like location data might be collected for non-essential services. You must give your users some control over this. Here's a great example of informed consent from Google:

Summary - Gaining Consent Under the GDPR

For consent to be meaningful under the GDPR, it must be:

- Freely given - don't try to "trick" you users into consenting. Don't withdraw any other services if they choose not to consent.

- Specific - if you want to process a person's consent for multiple purposes, you must ask them to consent to each type of processing.

- Informed - provide clear information about what the user is being asked to consent to, and what to do if they change their minds.

- Unambiguous - use clear and simple language and present a straightforward choice.

- Given via a clear affirmative action - never assume you have someone's consent until they have actively agreed to something.

And finally, once you have a person's consent, you should make it easy for them to withdraw it.