GDPR Consent Versus PIPEDA Consent

Consent is at the heart of the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). It's also at the heart of Canada's major privacy law, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA).

So what constitutes "consent" under each of these important privacy laws, and how does a company get it in a compliant way? For both laws, it all comes down to what's known as "meaningful consent."

Let's take a deeper look at how consent is similar and how it differs between these two influential privacy laws.

According to the GDPR and PIPEDA, organizations need someone's meaningful consent before they can capture, disclose, or store their personal data. What this means is that, before you handle someone's personal data in any way, they must understand:

- What data you plan on collecting

- Who you want to share it with, and

- Why you need this data in the first place

People have a right to control what happens to their personally-identifiable information and the right to make an informed choice as to whether they consent to your terms.

To be clear, "personal data" is essentially any information that can be used to identify a particular person.

Now let's look at consent under each of these laws.

- 1. Consent Under the GDPR

- 1.1. Checkboxes

- 1.2. "I Agree" Buttons With Dialogue

- 1.3. Consent Under PIPEDA

- 2. The 7 Guidelines for Meaningful Consent

- 2.1. Emphasize Critical Elements

- 2.2. Individual Control

- 2.3. Provide Clear Options

- 2.4. Be Dynamic

- 2.5. Think Like a Consumer

- 2.6. Promote Periodical Review

- 2.7. Take Responsibility

- 3. Summary

Consent Under the GDPR

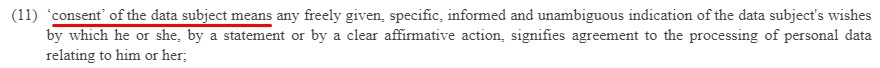

The GDPR's definition of consent is, at first glance, extremely strict. Under the GDPR, informed or meaningful consent is not enough. It must also be:

- Expressly given (implied consent is insufficient)

- Easily withdrawn

- Clear and unambiguous, and

- Very specific (there can be no doubt as to what a person is consenting to)

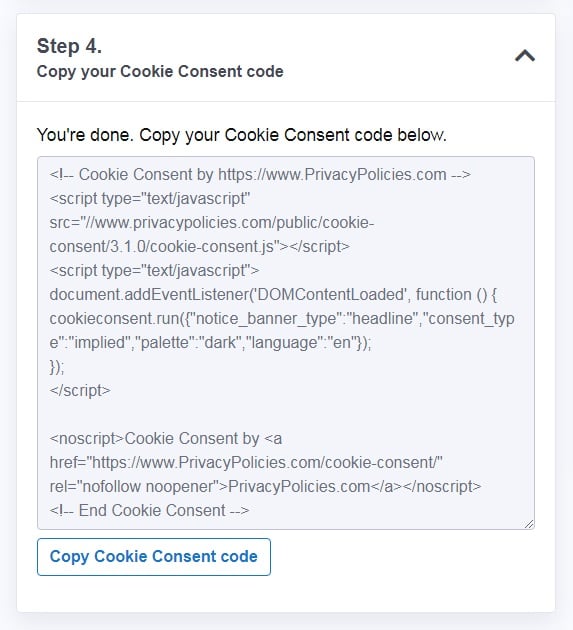

This is clearly set out in Article 4 Section 11 of the GDPR:

What this all means is that consent under the GDPR is only valid if it's obvious. Here's an example of what does and doesn't work under GDPR.

Checkboxes

A checkbox is a great way to get someone's consent to personal data processing, but only if it's clear, concise, and affirmative.

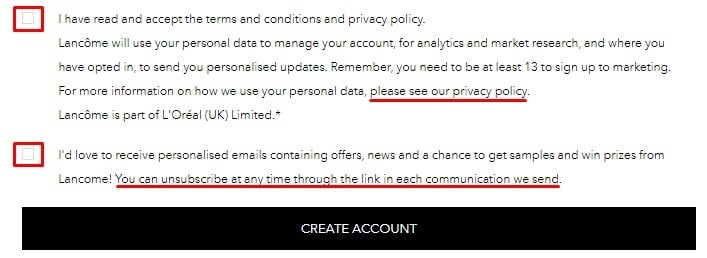

Let's look at an example from Lancome to show what we mean. Lancome uses checkboxes to get someone's consent to its Terms and Conditions/Privacy Policy, and to its marketing communications.

It uses two separate checkboxes - one for the Terms and Conditions/Privacy Policy, and another for marketing - so it's very clear what individuals are consenting to. A short description of how the personal information will be used is included, as well as a link to the full Privacy Policy.

Lancome also tells users how to unsubscribe at the same time consent is requested:

This is a great example of a GDPR-compliant consent tool. However, if the boxes were already pre-checked, it would not comply with the GDPR because then consent would be implied, not clearly given.

"I Agree" Buttons With Dialogue

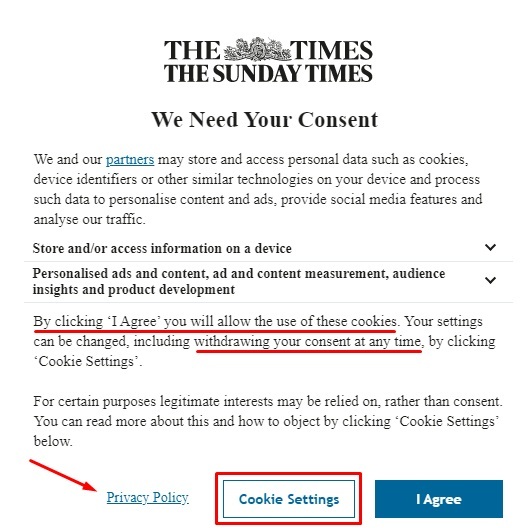

The Times has a pop-up box that requests consent from users to place cookies. The box doesn't include checkboxes, but it includes very clear statements letting users know that by clicking "I Agree" they are giving consent:

Users are also given access to a Privacy Policy link and a Cookie Settings section where they can learn more, and take more control over their options. They're also informed that they can withdraw consent at any time by going to the Settings section.

So, how does this compare with consent under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act? Let's take a look.

Consent Under PIPEDA

Although there are similarities between both acts, PIPEDA's required consent is far less comprehensive than GDPR consent.

Consent is set out in detail in Principle 4.3 of PIPEDA's Schedule 1.

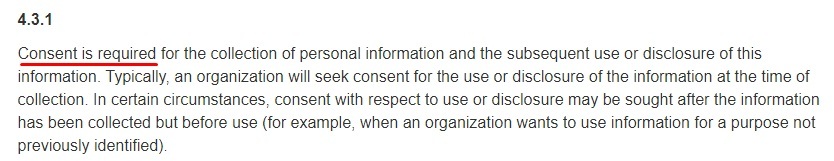

Principle 4.3.1 sets out what we already know - organizations should get an individual's consent to data collection before they actually collect it, except in very narrow circumstances:

Principle 4.3.2 deals with meaningful consent. You need to clearly set out how you plan on using or disclosing the information so that users know exactly what they are consenting to. You only need to take "reasonable" steps to set out what happens to the data.

"Reasonable" varies depending on your business needs and the sensitivity of the shared data:

Principle 4.3.5 is where we see something similar to the GDPR's "legitimate interest" concept, although it's not called the same. Simply put, you can use someone's personal data for a reason you didn't specify if a reasonable person would expect you to do so.

The Act sets out examples which makes this clear, but the gist of it is that you don't need to get consent for every single communication you might send a customer:

This all means that complying with PIPEDA isn't unduly onerous for a business.

Principle 4.3.6 is where we really see a deviation from the GDPR. Under Principle 4.3.6, implied consent is okay if the information isn't too sensitive. Unhelpfully, "sensitive" will vary by circumstance.

According to Principle 4.3.8, individuals have a right to withdraw consent. You will note that this is not quite the same as a user's right to be forgotten under the GDPR. It doesn't stretch so far, and it's also subject to contractual restrictions which don't apply under the European Regulation:

Now we're clear on what meaningful consent means in terms of PIPEDA, a question remains - how do companies actually get meaningful consent from their users and customers?

The 7 Guidelines for Meaningful Consent

Helpfully, the Canadian Government published seven guidelines to be read alongside PIPEDA on this issue. Let's look at them in turn.

Emphasize Critical Elements

You need to draft a Privacy Policy that's clear but comprehensive. It needs to be easy for users to find the information that they're looking for to give informed, meaningful consent.

To achieve this, put special emphasis on the critical elements, including:

- What information is collected

- How it's collected

- Why it's being collected or shared

- Who it's shared with

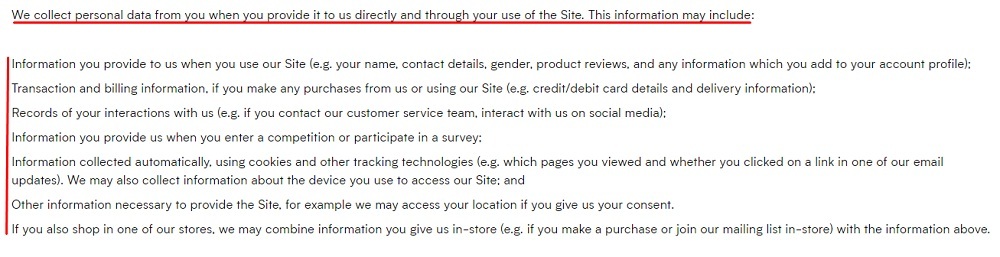

Let's look at an example. MyProtein uses its Privacy Policy to inform readers important things like what information is collected:

It then goes into what the personal information is used for:

Individual Control

The next point is that it should be easy for a user to choose how much detail they want. So, users who want to read your entire Privacy Policy in detail should be able to do so, but other users who only want to know the basics should be able to read this without skimming through your entire policy.

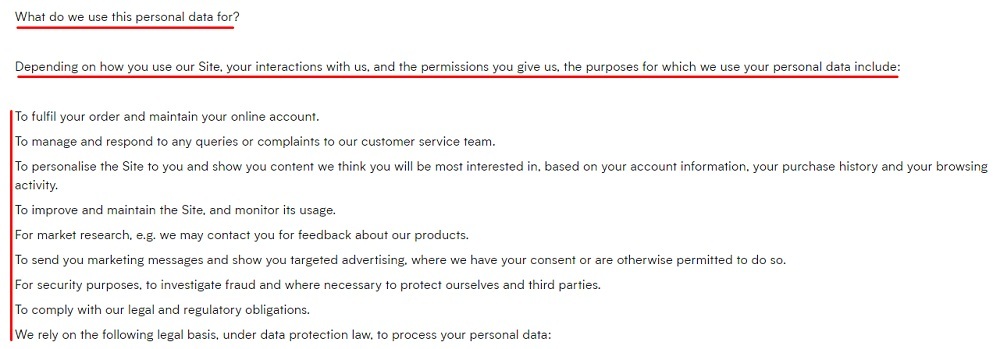

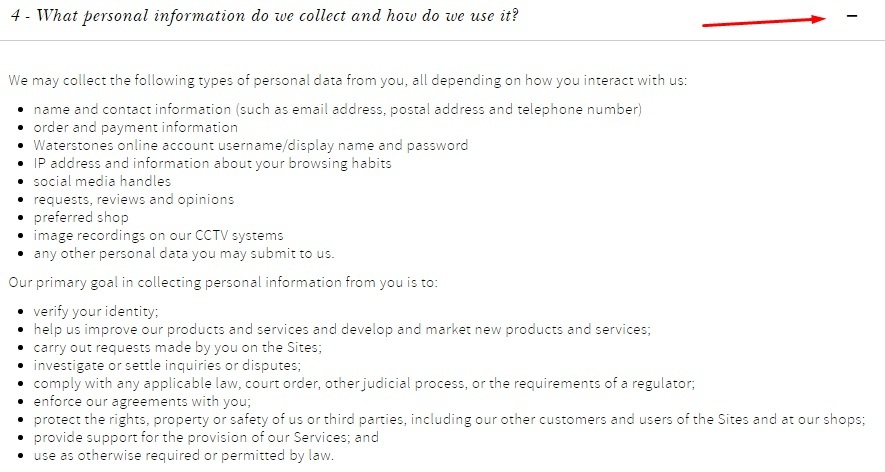

Waterstones breaks its Privacy Policy into small, readable sections that tell users exactly what they need to know:

Within each section, there's a clear explanation of what information is captured, why it's needed, and what happens to it:

Users don't need to read the whole policy to find information. Waterstones makes it easy for readers to skip to the sections they want to read.

Provide Clear Options

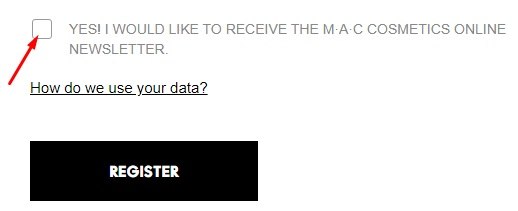

You can't demand or expect individuals to consent to non-essential information gathering i.e. marketing communications. You must give them a clear choice between, essentially, "yes" and "no."

Here's a simple example from MAC Cosmetics. Users physically mark a checkbox if they want marketing communications. Not checking the box constitutes a no:

Be Dynamic

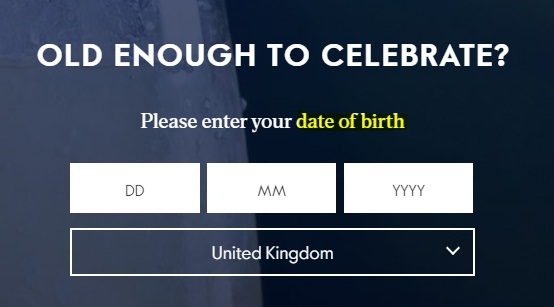

You should always be looking to obtain consent in new and creative ways that don't interrupt the user experience. This is easier demonstrated using an example. Let's pick an age-restricted site, such as an alcohol retailer.

Perhaps you want to check that someone's old enough to access your site or make a purchase. Grey Goose asks for a user's date of birth before they enter the site, and they use a friendly, simple format to get it:

If a user scrolls down, they can read the Privacy Policy before they enter any data.

Try to incorporate modern, simple notices and tools to obtain the consent you need.

Think Like a Consumer

What this all comes down to is that you should think like a consumer and keep things simple. Imagine you're shopping around a website or downloading an app. You don't want to pour over long-winded Privacy Policies or click through multiple menus to find out what you're looking for.

Instead, you want details in as user-friendly a way as possible. It's a good idea to:

- Do market research - Test your Privacy Policy and consent process and see how user-friendly people find them.

- Review your Privacy Policy and consent procedures regularly.

- Check if people understand what they're consenting to. This is the only way to ensure consent is meaningful.

Promote Periodical Review

You shouldn't just assume that user consent is final. Instead, you should:

- Review your Privacy Policy as your organization grows and evolves

- Audit your practices to ensure you're handling user data the way you claim to be

If you make any changes to your Privacy Policy, or change how you use data, highlight this on your website or send users an email informing them of the updates. Give them the opportunity to withdraw consent if they want.

Take Responsibility

Always be ready to demonstrate compliance to regulatory authorities, and make it clear to your customer base that you care about their privacy and their rights. You can do this by having a comprehensive, clear Privacy Policy that you follow.

Summary

Under PIPEDA and the GDPR, people must give their meaningful consent to companies capturing, sharing, or handling their personal information.

By updating your Privacy Policy to be informative and understandable, and using active methods to obtain consent (such as a checkbox), you'll be more likely to comply with both privacy laws.